West Yorkshire Local Transport Plan: A Summary

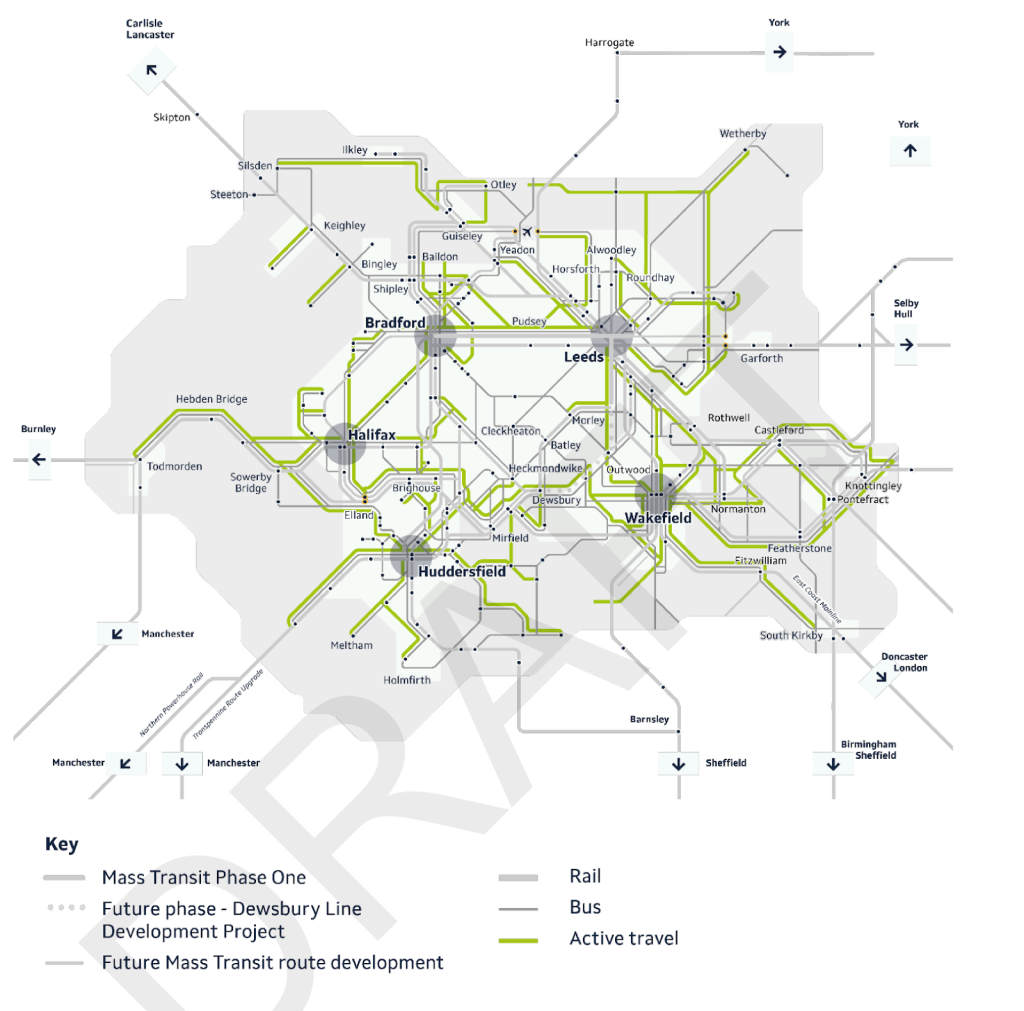

The draft West Yorkshire Local Transport Plan (LTP) sets out the Mayor’s vision for tackling the climate emergency, health inequalities, congestion, and safety through a rebalanced transport system. It introduces the Weaver Network, a connected system of mass transit, rail, bus, walking, wheeling, and cycling. The consultation is open until October 21, 2025.

The LTP will be supported by other policy documents, including an Active Travel Strategy and the long-awaited West Yorkshire Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plan (LCWIP), which is due for consultation in early January 2026. Both of these will hold more detailed information on policy and implementation around active travel.

At 122 pages, the draft plan isn’t light reading and much of it is repetitive. We’ve read every word so you don’t have to. The unavoidable conclusion is that we all need to use the car less. If the alternatives are made genuinely viable, this doesn’t have to mean new restrictions, but rather new choices. The case for change is overwhelming: congested roads that drag down productivity; toxic emissions fuelling climate change; health problems linked to inactivity; and the grim toll of deaths and illness from dirty air and road collisions.

What’s less clear is how we get from words to delivery. The targets for 2030 and 2038 look daunting, especially in places like Kirklees where meaningful infrastructure has barely started to appear. And without a sustainable transport commissioner—a post that every other Metro Mayor region already has—who is going to drive this forward and make sure the plan is more than just warm words? To make sense of the rest, we’ve grouped our summary under the main themes: Climate, Health, Safety, Space, Choice, Change, Network, and Implementation.

Climate Emergency

The plan recognises that the transport sector is the slowest to cut emissions and that new vehicle technology alone will not deliver. Without major change, the sector will exceed its carbon budget within a decade. The headline target is an 81% reduction in emissions by 2038, which will require rapid modal shift away from cars by 2030.

Health

Transport emissions contribute the majority of nitrogen oxides and particulate pollution locally. The LTP links active travel to cleaner air, reduced severance, quieter streets, and improved wellbeing. There is a welcome commitment to integrate greening, tree planting, and semi-natural spaces into transport and ‘place’ design.

The plan also recognises that the active part of active travel is vital in addressing inactivity, which is linked to a range of health issues including obesity, poor heart health, type 2 diabetes, and poor mental health. Beyond physical health, active travel can also reduce social exclusion and isolation, factors that are themselves associated with illnesses such as dementia.

Safety

In 2023, 45 people were killed and 1,450 seriously injured in West Yorkshire. The LTP promotes a Vision Zero approach to eliminate deaths and serious injuries through “safety by design”. However, it provides no detail on what this would actually look like, nor does it reference cities that have already achieved zero road deaths over 12 months, such as Oslo and Helsinki.

The LTP also avoids addressing the proven role of speed reduction in improving safety for all road users, perhaps an intentional omission to avoid pushback from those who view streets primarily from behind the wheel. It does recognise that concerns over personal safety and security remain a barrier to walking, wheeling, cycling, and using public transport, and commits to tackling these in order to support modal shift. Options mentioned include segregated cycling lanes on busy routes, reducing motor traffic in urban centres, and ensuring neighbourhoods are not dominated by through-traffic. The plan states that all users should have the “time and space” to move safely through design, signals, and markings, with a focus on those most at risk. However, the caveat “in the right locations” raises concern that this could be used as a loophole to limit interventions in areas where active travel journeys are currently low.

Space

The LTP acknowledges that our road network is under strain and that historical planning has favoured private cars, creating conflict between modes. Buses often lack priority because of limited street space, meaning they are frequently stuck in general traffic. The plan claims that how we use our streets varies depending on whether it is a major road, neighbourhood street, local high street, or town/city centre, though this distinction is often blurred in practice, for example in Kirklees.

The LTP notes that the role of our streets is shifting towards creating attractive and healthy places, rather than simply facilitating the rapid movement of high volumes of vehicles. If taken seriously, this could signal a move away from car-dominated planning. Car parking, particularly on-street parking, may be limited through place-based management to ensure kerb space serves people walking, wheeling, cycling, or using public transport. This principle could have major implications for schemes where infrastructure for pedestrians and cyclists is downgraded to mixed use to allow for residential car parking.

The plan also highlights the potential negative impact on vehicle capacity and local access when prioritising pedestrians. By separating this point from the wider strategic context—that reducing car use is essential to meeting climate and health targets—the LTP risks undermining its own argument and leaving space for decision-makers to defend the status quo, rather than pushing for stronger interventions that genuinely shift people out of private cars.

Choice

The plan commits to encouraging people to choose more sustainable modes of travel by making active travel a genuinely appealing and affordable alternative to car use, with infrastructure designed to meet or exceed national standards. It also promises to remove barriers to access by providing dropped kerbs, step-free routes, reduced street clutter, and safer environments.

Change

The LTP admits that West Yorkshire’s over-reliance on cars has created one of the most congested transport networks in the UK. It calls for a “major shift” to sustainable modes, including a 324% increase in cycling by 2038 (680% by 2030). It recognises that delivering high-quality transport infrastructure is essential for enabling modal shift and behaviour change, and that public transport and active travel options must be so well integrated that getting in the car for every journey is no longer the default choice.

Network

The plan commits to building a comprehensive, door-to-door active travel network woven into the Weaver Network, and accessible to children and young people. Priorities include: expanding infrastructure and reallocating road space; joining up currently disconnected routes; improving access for cycles, including adapted cycles; reducing through-traffic in neighbourhoods; and embedding safety in design.

The network will be supported by consistent branding, marketing, and wayfinding. It promises to make cities, large towns, local centres, suburbs, and out-of-town destinations accessible by walking, wheeling, cycling, and public transport.

However, the graphics for the proposed Weaver Network highlight significant gaps. For example, there is no provision around the Junction 27 retail park, home to Leeds’ IKEA, with no rail, mass transit or active travel connections extending as far as Birstall or Gildersome.Why Great Cities Let You (Easily!) Cycle to IKEA

Finally, the plan promises improvements to integrated ticketing. While any progress would be welcome, the real ambition should be a fully integrated system across all modes.

Construction & Implementation

The LTP stresses that the quality, safety, and functionality of the transport system depend on the condition of its underlying assets, including roads, pavements, cycleways, rail stations, and bus stops. It calls for a suitable maintenance and renewal programme. The current reality, however, is that maintenance has been lacking for active travel routes in Kirklees, with funding cut for Sustrans-managed paths and local routes becoming overgrown and having deteriorating surfaces. The document notes that minor defects that motor vehicles can easily handle pose major consequences for bicycles, especially those without suspension or with smaller tires.

The plan claims over 100 km of new or improved walking and cycling links have been delivered and that active travel is integrated into major funding schemes like the City Region Sustainable Transport Settlement. However, the document is considered noticeably vague on what has actually been delivered for cycling, in contrast to the detailed reporting on bringing buses back under local control. The timetable for future delivery is highly ambitious, with the LTP proposing to deliver a complete and fully integrated active travel and public transport network in just seven years (2025–2032), followed by phases to Grow the network’s market (2032–2037) and Enhance the network (2037–2040+).

To ensure a coordinated approach, the LTP commits to investing in line with the Streets for Everyone strategy. A Quality Management Strategy will be applied across programmes, with oversight provided by a Design Quality Panel to review interventions. This suggests a strong, welcome intention to establish consistency in design standards across West Yorkshire.

Despite this push for consistency, the plan acknowledges the need for flexibility, stating there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution, meaning interventions will be tailored to spatial constraints and local conditions. This flexibility, while understandable, carries the risk of inconsistent delivery, particularly if local political priorities do not align with the LTP’s wider objectives.

The Commissioner Gap

A central concern is the lack of a dedicated walking, cycling, and sustainable transport commissioner. This role, which exists in every other Metro Mayor region, would provide a single advocate to drive implementation, coordinate funding, and ensure accountability. The document concludes that the real test will be whether the Streets for Everyone strategy and governance structures alone are sufficient to deliver the network on time and translate the plan’s high ambitions into tangible, high-quality improvements across West Yorkshire.

toto slot slot gacor hari ini